Driver Reimbursement Application

Partnering with the DePaul Driehaus School of Business and a large B2B automotive service, I and two other human-computer interaction students researched the various ways in which people get reimbursed for their driving expenses while on the job. This project was done through the Design Thinking Group in the Innovation Lab at DePaul. Due to some institutional opaqueness, it’s unclear if this work was taken into the real world.

My role: Researcher, UI Designer

Timeline: 6 weeks

Context of the Problem

For many people in the United States, driving is still an essential part of their professional lives. Some companies will ask their employees to travel by car for their work, on the company budget; these people are then given funds retroactively in the form of reimbursements. Fleet management is a common element to many business models that require a decentralized supply chain, such as our client’s.

Currently, brands are presenting the logistics for capturing driver actions and delivering appropriate reimbursements in one of two major ways: asking drivers for raw mileage or automatically tracking drivers. These methods each have their respective flaws and benefits.

We talked with people who used either of these systems to broaden our understanding of how people interpret these services.

We adopted the 5-step Design Thinking process from the Stanford d.School: empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test.

Initial Goals and Assumptions

Tracking systems are nuanced based on respective technology stacks that support how companies track drivers’ miles, thus we had to assume variability between the expectations of how technology could serve participants.

One research goal from the B2B automotive service provider (our “client”) was to understand people's fear of "Big Brother" attitude toward automated tracking systems.

Participants

Recruiting for our study was done through a snowballing method; we decided to talk with 5 people. These people have different lines of professional work and use have varying levels of comfort with technology. This informed our primary differentiating factor for user segmentation.

Those who log miles via raw input.

Medical Field Technician. Drives about 2000 miles per month. Logs and submits miles monthly.

In-home Care Worker. Drives about 250 miles per month. Logs and submits miles monthly.

Salesman. Drives 150 per day. Logs data daily, submits miles monthly.

Those who do not use any system at all.

Regional Lottery Manager. Drives 300-600 miles per month. Logs miles in a notepad application.

Part-time Service Delivery Driver. Drives about 10 miles per day. Miles captured through service application which tracks position in background.

Empathize: Humans and Attitudes

We lined up the experiences from all of our participants, in a generic timeline to find out which pain points were most salient. The three “buckets” that we mapped the experiences under were Work Days, Logging Miles, and Getting Reimbursement. Some experiences were more beginning-to-end than others. Since participants engaged with their reimbursement systems in completely non-congruent ways, so defining a journey was neither feasible nor useful. Instead, we focused on their attitudes about how things worked for them.

Upon completion, we found everyone’s workday is entirely unique: people engage with company vehicle services on various platforms, with varying cadences. However, logging miles proved to be the only common occurrence. Through this exercise, we found that our designs should influence the task of logging miles to improve the overall experiences of the service because it was the common point of control.

Our major takeaways from synthesis activities were:

Keeping records in more than one places and having to transfer information caused frustration.

A perceived lack of flexibility restricted personal decision making.

People who logged miles daily were less pleased than those who logged miles monthly. These “daily loggers” did not trust their own reporting and felt inconvenienced.

When asked about automatic tracking systems:

"I think it would be great, since I don't trust my ability to record my miles. The less I have to do, the better."

Regional Lottery Manager.

"I'm afraid that it won't track me accurately and that I'll miss out on miles that I should be reimbursed for..."

Medical Field Technician.

Define: Future Design "Core Values"

Be Transparent

Show people how reimbursements are being calculated. Offering this information will establish deeper trust on the user's side.

Trust Your Users

People who are in the field are making decisions based on experience. Allowing for flexibility will make use-flows seem less restrictive.

Less is More

This service should not get in the way of what matters to users: getting reimbursements done with as little friction as possible. Design the application to require as little on-screen time.

Iterate

Informed by our preliminary synthesis, the group started brainstorming how the user interface might look and feel. Below are some of my sketches. The blue dots indicate certain elements that we carried through to prototyping.

Prototype and Test

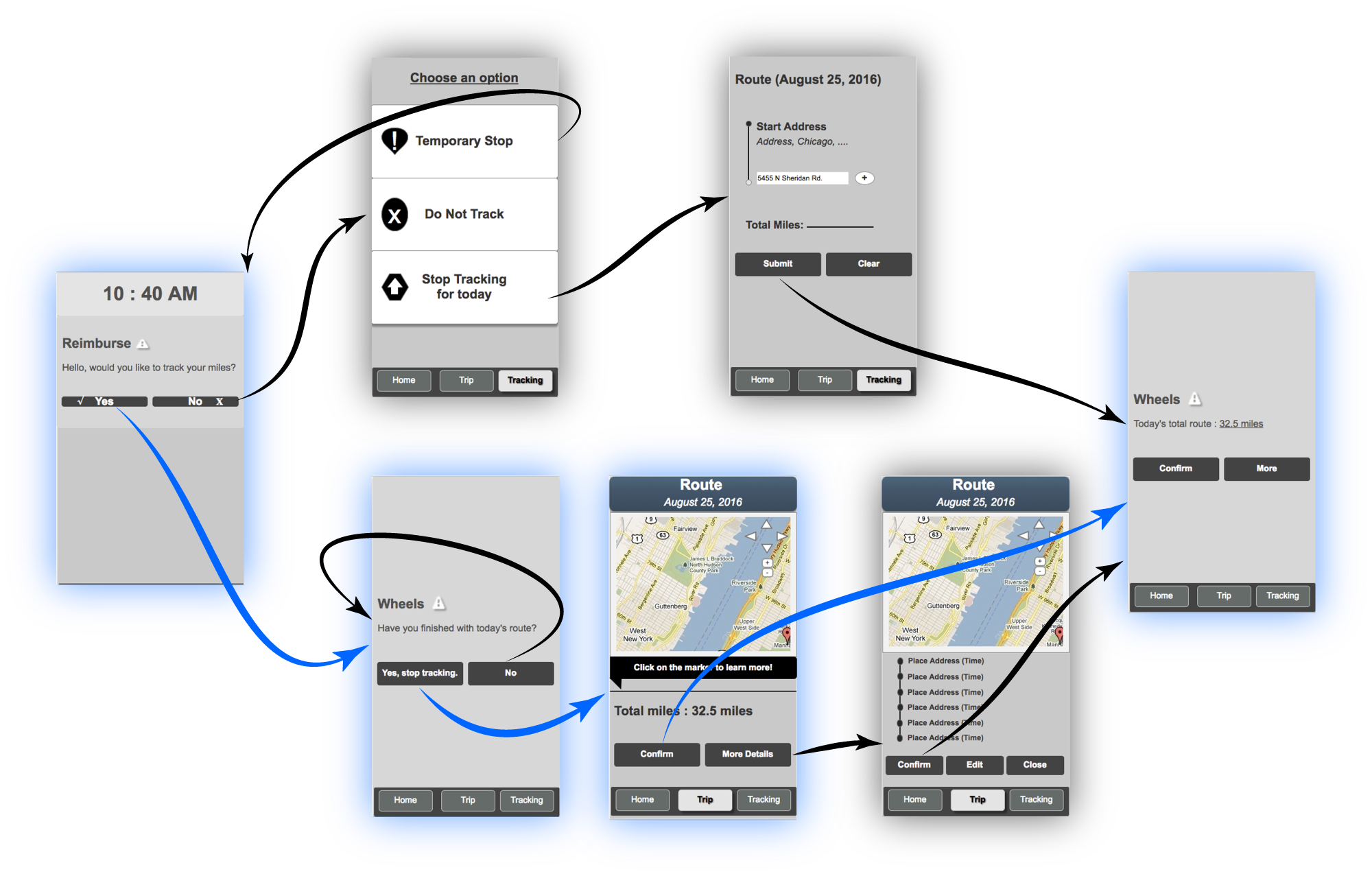

We gained early feedback from driver participants that there are ethical implications for over-surveillance, so our designs reflected the choice to either opt in or out of tracking. This validated an initial client assumption.

With a click-through prototype, we were able to perform basic usability testing and further inform how the application's design could potentially help people achieve their goals. We learned that the act of manually logging could potentially confuse drivers.

Finished renderings of application screens.

Team members: Tressa Bidelman and Mayi Nabine